Having earlier touched briefly on the Vienna Secession movement (What is the Vienna Secession? October 29, 2019) and on its connection with Art Nouveau in Vienna (toward the end of More Art Nouveau Notes: Time and Place, May 31, 2019), I continue to be intrigued by the links between the two.

Otto Wagner (1907)

Timewise, the two movements overlapped, with Art Nouveau coming on the scene as early as 1859 and lasting until the end of the First World War, while the Vienna Secession began in 1897. Indeed, some parts of the Vienna Secession continue to function even today. For example, there are still regular art exhibitions in the Secession building and it continues to be an important venue for visitors and the Viennese alike.

During many of the years preceding and concurrent with the Vienna Secession, art, architecture, and design in the Art Nouveau style was abundant in Vienna. That doesn’t bother me, and the more I see of work in Vienna designated as “Secessionist,” the less concerned I am that it may or may not be “Art Nouveau.” I’m inclined to simply relax and enjoy it all, regardless of how it’s labeled. Indeed, there is nothing not to enjoy, for all of these works – “Vienna Secession” or “Art Nouveau” – draw us in with their particular beauty.

Entrance

And while it would be a great pleasure – intellectually and visually – to go into a comparison with several different examples, one will suffice for now. Often referred to as “the most beautiful Art Nouveau church in the world,” the St. Leopold Church in Steinhof is, indeed, a spectacular house of worship. It resonates with the stunning beauty of the most successful examples of the Art Nouveau movement but also is a fine example of the exceptional talent of architect Otto Wagner, an early participant in the Secessionist movement.

Considered by many to be the primary Viennese architect of his day, Otto Wagner (1841-1918) probably continues to be the most famous of all the many architects, artists, and other talented designers who worked in both the Secessionist and Art Nouveau styles in Vienna. Indeed, it is hard to go anywhere in or near Vienna without finding examples of his work, or the work of some other architect showing his influence. Wagner built up a large following through his teaching at the Vienna Academy, where he taught from 1884 to 1913, and it seems that almost all the important Viennese architects of the late-19th or early-20th were his pupils at one time or another.

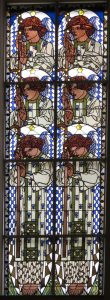

Side Window of the Church

The list of his commissions is far too long to give here. But for anyone planning a visit to Vienna, the trip would be incomplete without viewing some of his spectacular apartment buildings, for example, for which he chose decorative and definitively Art Nouveau details and ornamentation. Wagner was also responsible for the 36 stations of the famous Stadtbahn, or City Railway (1894-1901), including the special station built at the Schönbrunn Palace for the private use of the Imperial family, and the also the elegant Karlsplatz stations.

External Side Panel adjoining large window

When he designed the St. Leopold Church at Steinhof, Wagner concentrated on adhering to the already-accepted precepts of Art Nouveau. As it happened, the church turned out to be Wagner’s final commission. How the extreme praise repeated in the title of this post came to be is unknown, but it is frequently heard when the Kirche am Steinhof is described.

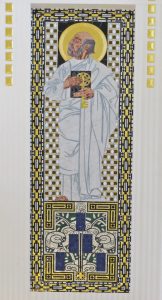

Side Mosaic at the Front of the Church

One needn’t even enter the church to be impressed, as the church is the culminating building of a large psychiatric hospital, the Psychiatrisches Krankenhaus (now called the Otto Wagner Spital). The church sets on a hilltop, offering a superb view of the surrounding countryside (and a breath-taking one as the visitor walks up to the church). The building was completed in 1907 and it really isn’t possible to separate the “most-beautiful” designation and declare that either the exterior or the interior is more beautiful. For example, the statues on the top of the front of the building (St. Leopold and St. Severin) were designed by Richard Luksch and their “thrones” by Joseph Hoffmann. It is notable for its marble exterior with nailhead ornamentation, and for the porch, supported by four stone columns topped by Jugendstil angels by Othmar Schminkowitz (an artist who must have been well known and well respected at the time, though I’ve been unable to find out anything more about him).

Angels on Porch Front Columns

Angels on Porch Front Columns

As for those four angels, here is where, in my opinion, the close affiliation between what we think of as the Secessionist style and Art Nouveau comes into play. They are so spectacular in their design and execution, and so beautiful to look at, that it becomes easy to see connections with both styles. Certainly, some of the so-called “linear” approach of Secessionism can be seen in several parts of the angels. If we take a close look at just the skirts of their gowns or the shawls thrown over their shoulders and arms, we can easily see bits and pieces that would not have shown up in an Art Nouveau design (or garment). On the other hand, if we’re trying to link Secessionism and Art Nouveau, that “flow” we look for in Art Nouveau is certainly present, both in the draping of the shawls I’ve already mentioned and the botanical sweep (an almost-universal characteristic of Art Nouveau) of the “feathers” of the angels’ wings. If we let our minds stretch a little, they could be giant leaves of some great bush blowing in the breeze. This, it would seem to me, is some of what comes into the minds of those who have come to think of the building as the world’s most beautiful Art Nouveau church.

In thinking about Otto Wagner’s work, for me the St. Leopold Church is a good place to begin. It is a story well told in Christian M. Nebehay’s Vienna: Architecture and Painting – 1900:

Angel Face (one of several) in Dome above Main Altar

In 1902 Wagner took part in a competition for the construction of the Lower Austrian Mental Hospital am Steinhof, later taken over by the City of Vienna. Wagner’s general layout was accepted, but not his plans for the individual pavilions.

He did, however, design the famous church overlooking the western approach to Vienna, which brought him international fame. Both the church and the asylum were built between 1905 and 1907. The church was meant for the use of patients, and the pews were so spaced as to allow the supervisors to intervene without difficulty. The glass windows were designed by Kolo Moser (1868-1918). The famous cupola is roofed with (originally gilded) copper plating. [N.B. In the intervening years since this was written, the church has been carefully restored, including the re-gilding of the dome. —GStC.]

Main Altar – Mosaic Resurrection with Saints

Having been built for the mental hospital’s patients, the interior of the church is almost overwhelmingly white, with white tile chosen for all surfaces (because, we are told, cleaning the tiles would not be a difficulty, as the white tile could be easily washed). Even more startling, at the side of the main aisle, the tiles are placed with a v-shape angle, to enable the washing-water to flow to the drains at the end of the aisle. Similarly, the holy water containers at the entrance to the church are designed so that the worshippers can push up on a lever which releases the holy water into their hands, and they are not putting their hands in a basin of holy water which, in some circumstances, might lead to the transfer of germs if present on the hands. Providing a stunning contrast, the daylight coming through Kolo Moser’s colorful stained glass windows provides a dramatic picture that, in and of itself, heightens the emotional beauty of the large single space of the sanctuary.

The mosaic work is in majolica, marble, enamel, and glass, designed by Remigius Geyling (1878-1974), but it was not completed until 1913. Of particular note are the tender child-like angel faces in the domed covering above the altar, the overall effect of which is to take the eye up to the magnificent arched mosaic. Even to the hospitalized patients who came to the church for regular worship services, the over-powering emotion must have been one of hope.

CLICK HERE TO SEE MORE PHOTOS: Vienna-Kirche-am-Steinhof

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wished to say that

I have truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. After all I’ll be subscribing to

your feed and I hope you write again soon!

Thanks for your comment. Keep reading. More posts coming.