Art Nouveau provides much pleasure to those who (like myself) have been captured by the allure of the style, and I think I might have come up with a reason why Art Nouveau is so appealing. It’s not only that the style provides the opportunity to experience exceptional beauty, however that elusive quality is defined by the viewer. At the same time, many of us find ourselves enlightened, for thinking about Art Nouveau also offers an occasion for delighting in some very specific intellectual edification (such pompous phraseology but you know what I mean).

I freely admit that this has been my experience over the years in my studies in Art Nouveau (as informal as they are). But like anyone who is enthusiastic about a topic and finds himself with limited time for exploring it, I’m also frequently disappointed that I can’t share what I’m finding with my friends. In fact, on this subject I’m even embarrassed, for it has now been two years since I shared any thoughts about Art Nouveau at this site. Over these two years I’ve engaged in much reading, many conversations with fellow enthusiasts, and any number of visits to as many exhibitions as I could find – both to museums and to galleries – for viewing examples of the style. But since that last post – A Deeper Dive into Art Nouveau, posted in March 2017 – I’ve not been writing about Art Nouveau.

I’m going to change that now, for I’ve been thinking about how (and perhaps even why) I’m so taken with Art Nouveau. In doing so, I’ve come up with a few attributes of the style that seem to explain its appeal for me. They start with time and place, as noted in this post’s title, but there’s more, which I will explore another time.

William Morris and Philip Webb

It’s no secret that timing, of course, was a particular element in the development of Art Nouveau. In the period starting in the mid-19thcentury, Art Nouveau had its earliest stirrings. It then moved closer to the mainstream and “advanced” (we might say) to the late part of the century when it began to be thought of as a style on its own. In the opinion of many scholars in the field, it was a “new” style, and English Art Nouveau (sometimes in England referred to as the “Modern Style”) started out in the work of William Morris, and in particular with Morris and Philip Webb’s Red House (of 1859) and what became known, from the work of his students, as the Arts and Crafts movement.

Willow Tea Room

A little later, moving toward the period when this new approach to art was being developed in other places, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife Margaret Macdonald were working with a similar approach – and possibly even more linear in their work – in Glasgow, leading to what would be recognized as having elements of Art Nouveau in its form and later being called the “Glasgow” version of Arts and Crafts. In America, with Louis Comfort Tiffany, the American artist most closely associated with Art Nouveau, the style became what we now characterize as “Tiffany” style, most represented in extraordinarily eye-catching glassware and, in particular, amazing lamps such as those displayed at the New York Historical Society (go here to enjoy “A New Light on Tiffany,” a one-minute video that can’t help but impress you with the beauty of the display as well as the depth of quality in our American version of Art Nouveau).

Back in Western Europe, it makes a certain amount of sense to focus on the time from the last quarter of the 19th century, when Art Nouveau caught on, to the First World War, when it effectively began to fade as a unique style. During this period, it played an important role in all the fine and applied arts. For me, I like to think about how Art Nouveau grew, starting out slowly as probably a group of one-off “trends” and then culminating with the Paris Exposition of 1900. It couldn’t be topped, and as Art Nouveau evolved into a way of looking at just about anything in a particular way after the exposition ended, it became clear (to us some 119 years later) that while it was to be a short-lived style, Art Nouveau came into its glory with the 1900 exposition.

Paris Exhibition 1900

by Philippe Jullian

And that’s not simply a modern explanation. Not long ago, I came across a copy of Philippe Jullian’s The Triumph of Art Nouveau: Paris Exhibition 1900 (New York. Larousse & Company, Inc., 1974) and it’s a fascinating story. With the many different “fairs” taking place in the major cities of the Western world throughout the 19th century, it is easy to see that they all were created to highlight Progress (clearly labelled with a capital “P”).

Transportation Building

World’s Columbian Exposition

Chicago 1893

For the United States, the primary formal expression of this Progress came in the splendid World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. The exposition as a whole certainly cannot be characterized as Art Nouveau (indeed, it was responsible for firmly establishing Beaux Arts architecture as the popular favorite for American architecture for decades to come). Even here, though, there was an Art Nouveau masterpiece in Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building, with its “Golden Door” entrance and other Art Nouveau detail.

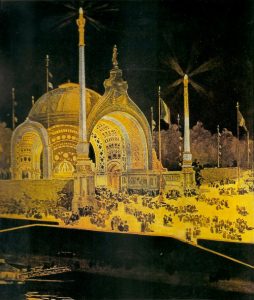

For all these fairs, the purpose was to demonstrate to all and sundry just how successful mankind had been right up to the date of the very opening of each exposition. For Paris, in 1900, there was a slightly different approach. Not only was Progress to be celebrated, the selection of architects, engineers, artists, and all other participants appears to have been inspired by a single visual theme: to create a “fairyland setting in ironwork and lit by electricity,” as Jullian’s book describes the overall look and “feel” of the 1900 Paris Exposition. Or, in another description, the exposition was “the triumph of Art Nouveau as an official style and of the electric lightbulb as a decorative emblem.”

Main Entrance

Paris Exposition 1900

Is there an example? Of course, and it would seem that the look of the entire operation would convey that fantasy-like sensation but there had to be one example that stood out. And there was: the very entrance to the show. Named for its architect René Binet, Porte Binet was the main entrance to the Paris World Exposition, and this depiction of the entrance by night (a watercolor by M.F. Bellenger, from Le Livre d’Or de L’Exposition de 1900) demonstrates clearly the fairyland approach. And why not? According to Jullian, Porte Binet, despite its fantasy-land look, “infuriated the Parisians.” Perhaps they simply weren’t prepared for such a visual leap into fantasy. Nevertheless, again according to Jullian, Porte Binet served an important purpose beyond being a fairyland entrance. It became, he wrote, “the symbol of the exhibition, the triumph of the Modern Style.”

Nancy, France

Like so much Art Nouveau, the Porte Binet did not draw on historical precedent, as had been the norm throughout the 19thcentury. It was this difference that made people uncomfortable. Personally, I would say, vive la différence! The floodgates had been now opened, and the Art Nouveau genie would not be put back in the bottle. Much was happening in many different locations, and I like to think about all that was going on in the minds of the designers (and their clients) in all these different places where Art Nouveau was taking hold.

Aveiro, Portugal

In fact, in the two years since I last wrote about Art Nouveau, I’ve come across a number of articles or other references to the locations of the burgeoning style, and I’ll share a couple that were particularly fascinating to me. The first was found in the travel guide of The Guardian and is described in Ten of the Best European Cities for Art Nouveau, by Jon Bryant on March 29, 2016. Take a look and see if you can resist wishing you could drop everything and head off to visit some of these places: Prague, Budapest, Glasgow, Turin, Brussels, Nancy, Darmstadt, Riga, Helsinki, and Aveiro.I want to go to every one of them, including a re-visit to Brussels (and to Art Nouveau jewels in Antwerp, while we’re so nearby), but none of them seem to “grab me” quite like Nancy in France and Aveiro in Portugal. I have not yet been to either, but these two especially are high on my list. I will get to them as soon as I can.

Art Nouveau: Utopia

And as we think about the critical importance of location and historical place in the development of Art Nouveau, there’s another list I find fascinating. It connects with the book Art Nouveau: Utopia – Reconciling the Irreconcilable, by Klaus-Jürgen Sembach. Published in Berlin in 1991 by Taschen, Sembach’s book points out that Art Nouveau’s practitioners “in a spirit of willful reform” made particular efforts to “distance themselves from the imitative historicism that characterized much 19th-century art and replace it with undulating, decorative qualities.” The book is a very special discourse on the history of Art Nouveau, special because it provides a hard (but not unpleasant) point of view. It gives the reader the opportunity to engage in a serious and perhaps more intellectual outlook about Art Nouveau and some of the results that have come from the admittedly short-lived success of the style. In the book, Sembach describes this effort as “turning to vine tendrils, flowering buds, and bird feathers as ornamental reference” in order to pursue “not only a linear freedom but also liberation from the weight of artistic tradition and expectation,” probably as lovely a description as any I’ve heard for Art Nouveau. Or for its raison d’être.

Secession Building

in Vienna

As an expert on Art Nouveau, Klaus-Jürgen Sembach’s career has given much successful attention to organizing exhibitions, but he is also renowned for his numerous publications on architecture, design, photography and film. At the same time, a review of what he has produced over the years (he was born in 1933) makes it clear that his is a scholarly and artistic perspective looking at and taking in at all sides of the story he is telling, and it is a point of view that makes Art Nouveau: Utopia – Reconciling the Irreconcilable a fascinating glimpse into the history of the style. He begins with describing how the movement began (“The Modern Style’s First Steps”) and he describes in exquisite details how Art Nouveau spread to different places, a direction he calls “Unrest: Uprising in the Provinces,” with the historical locations named and clearly described. They include Brussels, Nancy, Barcelona, Munich, Weimar, Darmstadt, Glasgow, Helsinki, and Chicago.

The climax of the book, taking my informal study of Art Nouveau to its next stage, is an essay Sembach calls “Equilibrium.” Its point is to use Vienna to demonstrate how, at the beginning of the last century, what we’ve come to know as both Art Nouveau and Vienna’s Secession Movement combined to provide us now with an exceptional appreciation of the new while not disdaining what came before. And Sembach is not dogmatic about the distinction between Art Nouveau and Secession. This final chapter of his book is subtitled “The Modern Style Arrives” and it tells us exactly what was happening. As he puts it in introducing the chapter, Sembach writes that:

After all that has been said, there may be some doubt as to whether Vienna’s contribution to the Modern Style around 1900 may still be classed as Art Nouveau. The lucid clarity so often found speaks against such an attribution, the continuing delight in rich ornamentation speaks for it. What emerges very clearly, however, was that Vienna was in many ways very different from the other European centres of Art Nouveau. The innovative dynamism found elsewhere was countered in Vienna by reflective maturity – the Dionysian element of sensuous functionalism by an Apollonian attitude of harmony and classicism. One who could not be relied on to conform – Joseph Maria Olbrich – took the consequences and left the city early on, for Darmstadt. No trouble was caused. That is, of course, too simple a reading of events, but it provides a useful introduction.

And that introduction took me to wonderful places when I was in Vienna. There will be more on this subject. Watch this space.

Leave a Reply