Two Memorials Honor the City’s Jewish Victims

When I find a city or other travel destination that has special appeal for me, I “fall hard.” Certainly that has been the case with Vienna. It’s been more than three years since my last visit, and despite several blog posts, I’ve come to realize that my many responses to this beloved city can’t really capture what I feel about Vienna. But I keep trying.

For this last visit, we were booked into the Park Hyatt Vienna, in the historic Inner Stadt, on Am Hof Square, the largest and oldest enclosed square in Vienna. Formerly the headquarters of the Austrian Hungarian Monarchy Bank, the building – now more than 100 years old – was recently re-built, intentionally restructured, we were told, “to preserve the history and aesthetics of the original structure.”

Of particular note is the near-by neighborhood known as Judenplatz, the site of the Jewish ghetto in medieval times. This important site is located at the end of the block on which the Park Hyatt Vienna stands, just a short walk from the hotel entrance. I found myself especially moved when I found this was where we could visit Vienna’s distinctive Holocaust Memorial.

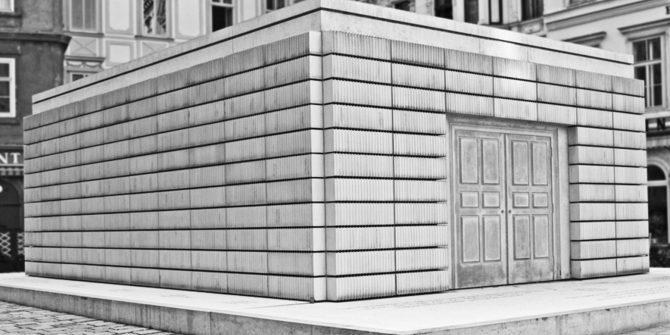

And that adjective is particularly relevant, for the memorial is absolutely distinctive. It sits among several historic buildings located in the Judenplatz, and the memorial can be seen, as one visitor put it, as simply a “giant square of stone.” Yet that “giant square” holds enormous meaning for all of Austria’s citizens – and the country’s visitors – with all that it represents, serving as a striking and painful reminder of one of the darkest times in world history.

Interestingly, the memorial stands on the Judenplatz just a few steps before the entrance to the annex to the Jewish Museum of Vienna. This building, known as Misrachi-Haus, contains exhibitions documenting the social, cultural, and religious lives of Viennese Jews.

But it is the memorial itself that draws the visitor’s attention. Of Vienna’s 200,000 Jews, more than 65,000 died in Nazi concentration camps, and the memorial is dedicated to them. Designed by Rachel Whiteread and unveiled in 2000, the memorial offers – at first – a puzzling design. It seems to look like a kind of upside-down library or collection of ancient research materials, with the sides showing rows and rows of books. Nearby, a wide plinth bears the names of the concentration camps where Austrian Jews perished, as well as a dedication to the victims in German, English and Hebrew.

Whiteread has described the purpose of such memorials, noting that they are created “to challenge and provoke thought.” Could that idea explain why, for example, the book spines face inwards, so their identity remains unknown? The concept decidedly matches what those of us viewing the Holocaust Memorial are thinking. Another source puts it this way: “The double doors are cast with the panels inside out, and have no doorknobs or handles. They suggest the possibility of coming and going, but do not open.”

Back at the hotel and moving in the opposite direction, away from the Judenplatz, we come across a very different memorial, one which – more than any other I’ve seen – captures the agony and humiliation directed at the terrified Jewish citizens of Vienna. It is meant to be a “walk-in” or “walk-through” memorial. Named the “Memorial Against War and Fascism,” it was erected in 1988, the Austrian year of reflection, and built as an initiative of Mayor Helmut Zilk, with Austrian sculptor Alfred Hrdlicka responsible for the design and execution.

The history of the site, a recognized historic neighborhood, is equally striking. And upsetting. The Philipphof, a large residential building, was located there, and in March, 1945, a bomb attack killed hundreds of people who were sheltering in the cellars. It was a horrible wartime situation, and many of the bodies could not be recovered. Indeed, the exact number of victims could never be established. Appropriately, the site was leveled in 1947. As the property on which the ruined building stood was owned by the state, it was not developed and became the park where the memorial now stands.

At the front of the park is the Gate of Violence. It is granite, known to have been dragged by thousands of prisoners over the so-called “death stairs” in the quarry of the Mauthausen concentration camp. One side commemorates the victims of the mass murders committed by the Nazis at Mauthausen and in other camps and prisons, as well as the victims of resistance and persecution for reasons of national, religious and ethnic origin, mental and physical disability, and sexual orientation. The figures on the right gate column are dedicated to the memory of all victims of the war.

And as is now well known, the earliest victims of the National Socialists when they were in charge were the Jews forced to clean the street on their knees, a disgusting situation clearly depicted by a bronze sculpture of a kneeling, street-washing Jew. It is a work of art that clearly shows the degradation and humiliation that came just after the Anschluss, and just before the extended persecutions and murders of Jewish citizens became worse.

Austria and the Austrians have been accused of minimizing their role in the Holocaust by presenting themselves as victims of Nazi aggression in the Anschluss. After the war, Western powers seeking a “buffer” with the Communist East chose to accept and even promote this point of view as a means of strengthening Austria. Monuments and memorials like these and others in Vienna are, at least in part, an effort to belatedly acknowledge historical fact.

Leave a Reply