[In brief.] Last spring, I had an experience in Milan that surprised me and left me thinking about the effect of remembering things that had happened earlier in my life. My years at university (in his case the University of Virginia in Charlottesville) took place a long time ago, and as with most people, it had been a natural process for thoughts about those years to slip away. In Milan, though, viewing a well-known work of art at one of the city’s most famous art collections had an unforeseen effect. I went to Milan’s Venerando Biblioteca Ambrosiana to see the cartoon for Raphael’s fresco “The School of Athens,” and I found myself unexpectedly taken back to my days in Charlottesville. At The University (as Virginians referred to UVA then), I had seen a copy of the painting on many occasions when attending events and school functions in Cabell Hall, the university’s auditorium. This post describes how viewing the cartoon in Milan took me back to my university days, creating a bridge between the present and those days of more than sixty years ago.

Memory as Frame of Reference

Of course, one of the primary literary examples of a current experience prompting memories of the past is Marcel Proust’s tea-dipped madeleine, which led to the recollections that comprised his multi-volume masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time.

Such is the case with this essay. My “madeleine” experience came in Milan when I first viewed the cartoon for “The School of Athens” by Raffaello Sanzio (1483-1520), generally referred to simply as Raphael. I was with Andrew Berner and Sandra Kitt and we had the sheer joy of viewing the cartoon together. It took me back to my first days—sixty-six years ago—at Thomas Jefferson’s University of Virginia, where I was to be a student.

I don’t expect to write a multi-volume literary classic, but to satisfy a request from some friends, I hope to take a look back at my university days. This post might be a first step to writing that memoir. When I was teaching for several years at Columbia University, students would comment about my teaching “style.” And as we conversed about “how” I taught, it seemed that some attributes of my teaching style were different from other contemporary faculty members, and from how 21st century teachers might be expected to teach. And the more we talked, the more we realized that how I taught related to my education in Charlottesville so many years ago.

At the time, I wasn’t really aware of these differences. They seemed to be clear to others, and soon I was being asked to explore and perhaps even write about my years at UVA (as it’s now known). When I was there, it was known simply “The University” or even as “Mr. Jefferson’s University” from some of our older faculty members and more tradition-focused students.

So after hearing from former students (some of whom became friends and remain friends), after reading Proust, and, yes, even after thinking about enjoying some of my own “remembrances of things past,” I will begin a memoir of my days on the Grounds (never “the campus”) of The University of Virginia. So this essay might be the introduction to the memoir.

The School of Athens Cartoon

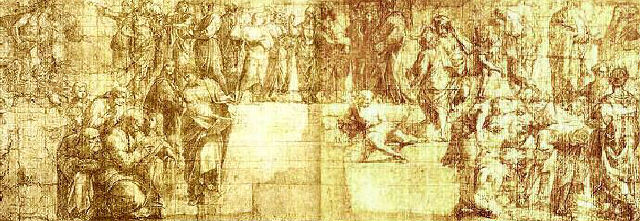

Raphael’s work is described as follows by the Venerando Biblioteca Ambrosiana, and to demonstrate that restoration was necessary, we have the 2004 photograph above.

This drawing is certainly one of the most precious artworks in the collection and in the city of Milan. It is the largest Renaissance cartoon that has survived to this day, and was made by Raphael as a preparatory work for the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican, which was commissioned by Julius II. It entered Federico Borromeo’s collection in 1626, when he purchased it from the widow of Fabio Borromeo Visconti for the massive sum of six hundred imperial lire, even though it had actually been on loan to the Ambrosiana since 1610. Although it is known as The School of Athens, the more exact title is Philosophy, as suggested by the allegory of the same subject painted on the vault above the fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura, as part of a very complex iconographic project. At the centre we see the two greatest philosophers, Plato (painted with the likeness of Leonardo, with his finger pointing upwards and identifiable by the Timaeus he is holding, one of his works that had enormous influence on later philosophy) and Aristotle, who is identified by his book of Ethics.

When the four-year restoration was completed, the cartoon was returned to public view.

Elisabetta Povoledo, writing in The New York Times on March 26, 2019, captured the excitement of having the cartoon back on display:

Preparatory cartoons for Renaissance frescoes—the full-scale drawings that artists used to transfer their designs to the wall—rarely survived the finished commission. Functional and fragile, they weren’t meant for posterity.

But thankfully, Raphael’s cartoon for “The School of Athens,” a famous fresco in the Vatican, survived.

Commissioned in 1508, the fresco is part of the decoration of a suite of four rooms in the Pontifical Palace—now known as Raphael’s Rooms—that Pope Julius II used as his residence. Along with the Sistine Chapel, these rooms are among the Vatican’s biggest draws.

The boldly colored fresco was painted by Raphael and his assistants, and is set just above eye level. The cartoon, however, was drawn by Raphael alone, and the new layout of the room that houses it—now placed inside a state-of-the-art vitrine with nonreflective glass—lets visitors get up close enough to detect individual charcoal strokes and shading.

This week the cartoon for the “School of Athens” has gone on public view again after a four-year restoration by the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, an art gallery in Milan that has had the cartoon in its collection for some 400 years.

Andrew Berner, writing about the cartoon in another context, described the technical distinctions of the cartoon

Another of the great treasures of the Ambrosiana was just a few steps away in a room of its own. This was the cartoon created by Raphael for his massive fresco, The School of Athens, in the Vatican. The term “cartoon” can be confusing given its more modern meaning, but in this case it refers to the preparatory drawings that were created for the execution of a large fresco. Since frescos must be painted onto wet plaster (something that Leonardo chose to ignore, causing huge problems with his Last Supper) each individual sheet (the edges of which can be discerned in the photo) represents the amount of work that could be accomplished in a single day. There were hundreds of them, each bearing a full-scale rendering of a small section of the finished work. Pin pricks would be made in the paper following the lines of the rendering. The wet plaster would be applied to the wall (or ceiling) and a section of the cartoon would be attached to it. Bags of pulverized charcoal would be pounded against the cartoon, the charcoal passing through the pin pricks, and leaving a dotted outline for the finished work. Section by section, day by day, this process would be repeated. Usually, once the fresco had been completed, the sheets of the cartoon would have been discarded. It is not unique, but it is certainly uncommon for all of those for The School of Athens to have been retained.

We entered the darkened room, and on the far side, across a large wall—and beautifully lit—were all of the sections of the cartoon for The School of Athens, in total as large as the finished work. The existence of the full cartoon is significant in a number of ways, but perhaps most important, it reveals to us a change that was made in Raphael’s original plan. In the cartoon, there is a section to the left of center where the stairs (crowded with figures elsewhere) are empty. If you are familiar with the finished work you will know that Raphael made a “last-minute” addition to his original plan. While Raphael was working on The School of Athens, Michelangelo had completed his work at the Sistine Chapel. The genius of Michelangelo was so evident to Raphael, that in his final version of the fresco he chose to fill that space with a very prominent depiction of Michelangelo in the foreground.

Below, we have a view of Pinacoteca Ambrosiana visitors in front of the cartoon, clearly demonstrating the cartoon’s gigantic size (and that of the finished painting in the Vatican).

As we think about the original painting, it becomes very easy to understand why it is considered on of the great artworks of Western society and specifically of its period, the Renaissance.

Guy’s First Days at Mr. Jefferson’s University

How, then, do we connect all this beauty and this great work art to Guy’s first impressions of The University? And how did Guy’s first sight of the cartoon for “The School of Athens” become that memory trigger it turned out to be?

Here’s how it happened: After my parents and I had completed all my moving-in chores for Kent House, the beautiful new dormitory I would be living in for my first year, they left to drive back to Radford, the town in Southwestern Virginia where we were living at the time. I was left on my own and I made a very specific decision to walk around the Grounds, to get to know this beautiful place as well as I could before the beginning of classes in the second week. I had a week to get to know my new surroundings, and I wanted to take full advantage of the time I had.

I started with The University’s famous Rotunda, designed by Jefferson and located at the northern end of his planned “Academical Village,” as he thought of it. The University had been established in 1819 but because of delays, the Rotunda was unfinished when Jefferson died in 1828 and construction took several more years.

Still, when the Rotunda did open, as The University’s library, it was a very grand building. An Annex, with classrooms and a 1,200-seat auditorium, was later built in 1853. It had a copy of Raphael’s “The School of Athens,” painted by renowned French copyist Paul Balze. The words above the stage, from Virgil’s Aeneid, are commonly translated to “A joy it will be one day, perhaps, to remember even this.”

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Virginia

Sadly (and to add to the historical romance of these early days at The University), faulty electrical wiring in the Rotunda Annex caused a fire in 1895. The fire destroyed the Annex, along with the mural. In their later design for Cabell Hall architects McKim, Mead & White commissioned a replacement copy that would be incorporated into their new building. George W. Breck, a muralist from New York who later served as director of the American Academy in Rome, completed the replacement mural in 1902. Breck made his mural four inches off scale from the original in Rome, to comply with a Vatican policy prohibiting exact copies of its original artwork.

So as I continued walking about the Grounds, determined to see all I could see before classes began, of course I walked several times down the Lawn. As I had my own special interest in music and what my musical life at The University might become, and as I had learned that the Music Department was located in Cabell Hall, of course I went there.

Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Virginia

And that’s when it happened. On my first visit to Cabell Hall, I discovered to my surprise, that it was open, and I could walk right in the front door. I looked around, fascinated by being in this beautiful building during my first day at The University, and there it was. The doors to the auditorium were not locked, and I went in and, for the first time, I saw the magnificent copy of “The School of Athens,” never expecting that it would become such a vital part of my life.

Of course it did, and I was there often, always focusing my attention (no matter the real purpose of my being in the auditorium) on the painting. Many meetings were held there, open to students (sometimes with required—or expected—attendance).

On other occasions, concerts, speeches from political and national leaders, and oral readings took place in the space, and I can’t begin to list all the classical musicians the various musical agencies brought to Cabell Hall, including many opera stars as they made their performance tours across America. Not to be ignored, of course, were programs by The University Glee Club, its band, the Charlottesville Chorus, and a wide variety of student and faculty chamber music groups and soloists. And of course any number of other university-related performances took place. In fact one of the first performances I heard in the Cabell Hall auditorium was by The University’s orchestra (which explains why I was delighted to find this photo, as it was very typical of what the hall looked like when I attended musical events there). And, not to put too fine a point on it, Cabell Hall was easily accessible, in a central location with the students’ dining hall just a couple of buildings away.

Yes, “The School of Athens” was important to me, although I had forgotten about it for many years until I discovered it again with the cartoon in Milan.

And what memories did it evoke?

Certainly, at this point in time, far too many to try to bring up, but I can say—pretty confidently—that my time at The University of Virginia was a good time for me, probably the happiest time I had ever had in my young life (and perhaps even beyond). It isn’t necessary to go into specifics but I expect they have something to do with learning, with being on my own and living “my own life” for the first time. And—without making too much of it—probably exactly what every young person realizes when he or she is given the opportunity to think about that first happy time and is able to recognize it for what it is.

But I didn’t think about it alone. Sometime after that visit to Milan, a friend and I were talking about the experience. She made a remark that probably more than anything else captured what it meant to me to see Raphael’s cartoon at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana / Pinacoteca Ambrosiana.

“It took you back,” she said. “It helped you recognize once again how your time at The University ignited your curiosity. It’s still a strong part of you, of who you are and how you think. It’s what makes you you.”

Leave a Reply