There aren’t many times we get so caught up in an exhibition that we’re afraid we’ll get locked in.

That’s what happened to me the afternoon I spent at “Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind.”

And just to get my complaint out of the way first: This wonderful exhibition – one of the NYPL’s best – is crammed into a tiny space, and if there are more then ten people in the room, it is really hard to move around, much less learn much from viewing the objects on display and reading the legends. The site is the Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Gallery, on the main floor of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building (what we used to call “The Main Building” or “The 42nd Street Building”) of the New York Public Library. Many thanks to the Wachenheims and to Mr. Schwarzman for the space. It’s fine for some exhibitions but, sadly, the space is really cramped for an exhibition as full of content and learning as “Over Here.”

And just to get my complaint out of the way first: This wonderful exhibition – one of the NYPL’s best – is crammed into a tiny space, and if there are more then ten people in the room, it is really hard to move around, much less learn much from viewing the objects on display and reading the legends. The site is the Sue and Edgar Wachenheim III Gallery, on the main floor of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building (what we used to call “The Main Building” or “The 42nd Street Building”) of the New York Public Library. Many thanks to the Wachenheims and to Mr. Schwarzman for the space. It’s fine for some exhibitions but, sadly, the space is really cramped for an exhibition as full of content and learning as “Over Here.”

OK. Complaint over. This is truly an amazing exhibition and it’s on until February 15, 2015. And from what I’ve written, you can see that I think it’s worth the effort to get into the exhibition and spend time taking it in. Visit the exhibition, and if you’re able to go when there aren’t many people about, you’ll find yourself caught up in massive amounts of content about what was going on in the United States in the years leading up to and during our country’s involvement in World War I.

The subtitle for the exhibition tells us what it’s all about, the huge public debate at the time, as Americans struggled (and argued, sometimes not very pleasantly) about whether or not the country should be involved in the war. As the exhibition guide describes what was going on, the debate “was facilitated by an unprecedented array of media and performance outlets, including such recent inventions as recorded sound and motion pictures.”

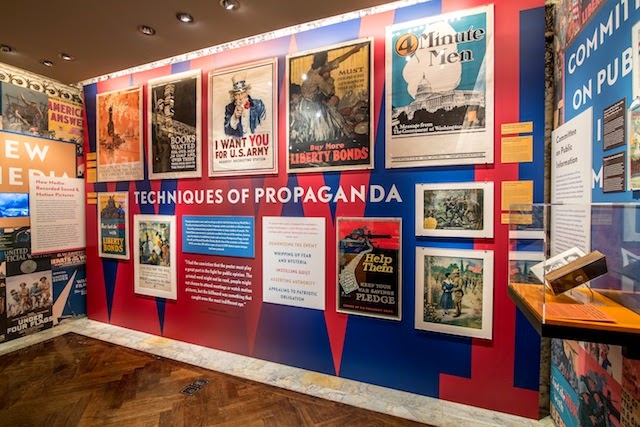

The result is an intellectual exploration – using materials from the NYPL collections – that teaches us a great deal about how public relations, propaganda, and mass media were used to “shape and control” public opinion. As you spend time with these items, you get the idea that such methods had not previously been used – at least not to such an extent – in any situation in which Americans found themselves. We learn about how “100% Americanism” became the popular phrase of the time, building a “hyperpatriotic” attitude (in the words of the exhibition guide’s writers), and the whole shift from absolute neutrality (personified by the activities and leadership of Jane Addams) to total involvement (led by former President Theodore Roosevelt).

The result is an intellectual exploration – using materials from the NYPL collections – that teaches us a great deal about how public relations, propaganda, and mass media were used to “shape and control” public opinion. As you spend time with these items, you get the idea that such methods had not previously been used – at least not to such an extent – in any situation in which Americans found themselves. We learn about how “100% Americanism” became the popular phrase of the time, building a “hyperpatriotic” attitude (in the words of the exhibition guide’s writers), and the whole shift from absolute neutrality (personified by the activities and leadership of Jane Addams) to total involvement (led by former President Theodore Roosevelt).

And needless to say, I loved that the cover of one piece of sheet music (left) was used as the wall-size poster to lead visitors into the exhibition (right). An impressive transfer indeed.

[Note: all images courtesy of The New York Public Library.]

For me, there were three special conclusions I took from the exhibition. The first – which I had not realized before – was that idea of “100% Americanism” I referred to above. Again taking a leaf from the exhibition guide, I was surprised to learn that “never before in the country’s history had Americans been so widely, and energetically, courted. And never in its history had the concept of Americanism – of what it means to be an American – been so hotly contested.” Is there, I might ask, some sort of connection between what in our time we hear referred to as American “exceptionalism” and this extreme pro-and-con discussion about patriotic loyalty? Did this sort of thing start with our citizens up to and during World War I? Certainly that subtitle (“WWI and the Fight for the American Mind”) clues us in that this sort of thing had not been done before. And look where we are now, in the “fight” for the American mind.

The second conclusion I reached has to do with the amazing role of advertising, public relations, and similar citizen-influencing activities. While many of these started out – as noted – as individual or group activities taking advantage of the various new communications techniques, the effort became “official” on April 14, 1917 with the establishment of the Committee on Public Information (known as “the CIP”), created to bring the American people – willing or not – into supporting and participating in the war effort. And a result of this effort – again a new revelation for me, as I had not known this before – was the birth of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Founded in 1917 as the National Civil Liberties Bureau (CLB), the organization’s main purpose was freedom of speech, especially anti-war speech, and on defending conscientious objectors. I had no idea this was where ACLU came from, but after viewing “Over Here” and learning about the particular tenor of the times, it’s no surprise.

The second conclusion I reached has to do with the amazing role of advertising, public relations, and similar citizen-influencing activities. While many of these started out – as noted – as individual or group activities taking advantage of the various new communications techniques, the effort became “official” on April 14, 1917 with the establishment of the Committee on Public Information (known as “the CIP”), created to bring the American people – willing or not – into supporting and participating in the war effort. And a result of this effort – again a new revelation for me, as I had not known this before – was the birth of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Founded in 1917 as the National Civil Liberties Bureau (CLB), the organization’s main purpose was freedom of speech, especially anti-war speech, and on defending conscientious objectors. I had no idea this was where ACLU came from, but after viewing “Over Here” and learning about the particular tenor of the times, it’s no surprise.

And the third thing that impressed me? No surprise here. I just hadn’t thought about it before: the amazing growth and influence of posters as a means of communicating a particular point of view. The exhibition notes point out that the American government became especially proficient in communicating “targeted information to large numbers of people,” using such artists as James Montgomery Flagg, Joseph Pennell, and Howard Chandler Christy. Not only proficient but prolific: by the end of the war, more than 20 million copies of some 2,500 distinct poster designs had been produced. As George Creel explained it in his 1920 book How We Advertised America, even those of us of a later era can see why posters were so important:

I had the conviction that the poster must play a great part in the fight for pubic opinion. The printed word might not be read, people might not choose to attend meetings or watch motion pictures, but the billboard was something that caught even the most indifferent eye.

So I suppose visiting “Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind” supports what I learned at the program (described here on December 11) at the Morgan Library and Museum, that World War I – despite what we think about it and read about and attempt to learn about, that war really did move us as a society from a way of life to one that was totally different after the war. Nothing was to be ever the same anymore, especially – as evidenced in this fine exhibition – how we’ve learned to live with a vastly different way of life as we moved toward and into the 21st century. Lots to think about.

Leave a Reply