It’s Midsummer’s Day today, and as I prepare to send this post out (hopefully before Midsummer’s Day turns into a dreamy midsummer’s night), I have to confess that I was shocked to see that my last post was on Easter, some three months ago. My apologies.

I’m consistently thinking about how lucky I am. Not just for my friends and professional colleagues (for I am very blessed with that accumulation of good people who surround me), but in the many environments and activities that I have as part of my life. A colleague recently referred to these personal posts as “Guy’s thoughts – on all the things he thinks about” – and that’s a pretty fair description.

I’ve been thinking of all the things that drive me, all those interests that my mind habitually grabs on to, and while I’m very lucky to have so many friends and students and colleagues with whom to speak about these things, I also get a great deal of pleasure in thinking about how these “drivers” (to continue the construct) are ranked in my own mind. And while the obvious ones are known, as I indicate above about opera, to just about anyone who knows me, there’s always my love of and concerns about elephants, those magnificent creatures that simply by existing and moving about as they do, bring immense joy and gratitude to those of us who have been fortunate enough to observe them in the wild. I never forget about my elephants. Even in zoos. When I visited this lady in the zoo in Rome, I was truly convinced when I had the opportunity to spend some time in her presence (safely on the other side of the fence), that she and I shared a certain spark. I get a tremendous amount of pleasure in simply observing how these animals move about. And when they observe us in return.

And then there’s my almost passionate love of Art Nouveau. I can’t stop thinking about Art Nouveau, and almost everywhere I go I look for examples (see below) and even if what I’m able to look at is something relatively minor and not at all along the “usual” lines of Art Nouveau, I delight in looking, studying (I can be very boring when I stand in front of some rather innocuous example of Art Nouveau), and sometimes those with me wonder a little bit about what has captured my thoughts so intensely. Imagine my surprise when visiting Venice – where I did not expect to find any examples of Art Nouveau – to light upon a tiny colony of very grand old villa on the Lido that had been built for the very wealthy in the early part of the last century (think the Grand Hotel des Bains in Visconti’s “Death in Venice”), along with several rather palatial private homes, obviously built for the well-to-do (such as the one pictured here). And even more surprising, a suite of Art Nouveau furniture (in the “Liberty” style, as Art Nouveau is characterized in Italy) found at International Gallery of Modern Art at Ca’ Pesaro. I’ll be devoting another post to Art Nouveau in Venice, so not too much here.

But there’s more, and it’s really a little hard to “slow down” (perhaps not the best phrase for what I’m trying to express here) and think about other things that capture my thoughts. For one thing, of course, nowadays the truly big one (almost to the point of being a nuisance) has to do with what’s going on in society, not only in our lives, not just in America, but in the larger global community. We’re all very frightened. Or most of us, those who are determined to think realistically about what’s happening in today’s society.

I touched on this some months ago, and this – not to be too pedantic about it – was ‘way before we were experiencing the deluge of commentary about the fearful situation we have before us today. I honestly don’t know how we can keep up, those of us who want to be informed. I try to read Foreign Affairs and The Economist, usually The New Yorker, and, yes (I’m a New Yorker after all) The New York Times, but there is just no way I can handle it all. But it has to be handled, and we all must think about it. As I say, before we – as a society – were as frightened as we are today – I took a few baby steps (for Mr. Guy) in one of my podcasts.

In the podcast, I was speaking about management and how we might connect the bigger effort of how we function in society with management (as a professional discipline) and knowledge services, my specialization and the subject I teach. The podcast title was Management: Science or Art? What’s the Purpose of Management? (the text of the podcast is also available as one of our corporate blog posts, accessible here) and I was attempting to see how we might think about management and what is happening in the larger world beyond our immediate workplace or environment.

I made reference to having heard David Miliband, the President and CEO of the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and himself from a refugee background, He had came to the job after his work in Parliament, first as Environment Secretary, during which short term climate change became a priority for policymakers, and then he was promoted to Foreign Secretary, a position he held until April 2013 when he resigned to come to New York to lead the IRC. In his talk with us, Miliband reminded us about the importance of the meeting between Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt in Newfoundland in August of 1941, a meeting which led to what soon became known as the Atlantic Charter. It was a critically important policy statement, and particularly at that time, for it defined (even though the United States was not even in the war yet) the Allied goals for life after the war. Ultimately, once all the Allies had signed on — which happened very quickly, on January 1, 1942 — the Atlantic Charter became the foundation of the modern United Nations.

Miliband’s visit got me to thinking about my long-standing interest in the Marshall Plan and what it meant for the European nations after World War II, a lesson brought home to me when I lived in England back in the 1980s. In Canterbury, at a gathering at which I was the only American, the conversation got around to the amazing affection (I had been noticing) the British people I met were demonstrating for Americans. So I asked why this very positive and almost admiring point of view was being shown by English friends to me and to the other Americans I ran with. The hostess, a wonderful lady now nearly 100 years old, spoke up. It was one of those quiet moments you have at every party, when everything is suddenly silent and everyone is listening to the single person speaking. She said, without missing a beat, “It was the Marshall Plan.”

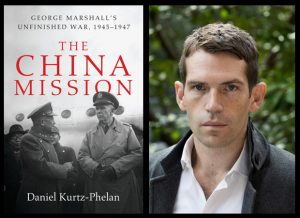

The China Mission

Her response opened a door for me, and I became a passionate student of everything I could find out about the Marshall Plan, and now I’m interested to see that there is more, that few of us knew about, for now Daniel Kurtz-Phelan, Executive Editor of Foreign Affairs has just published a book called The China Mission: George Marshall’s Unfinished War, 1945-1947. I haven’t had a chance to read the book (or even much about it) yet, except to learn that President Truman, before the development of what became the Marshall Plan, had charged Chief of Staff of the United States Army and later Secretary of State George C. Marshall to use his expertise for helping China. As the publisher’s description states, “the conflict between Chinese Nationalists and Communists threatened to suck in the United States and escalate into revolution. [Marshall’s] assignment was to broker a peace, build a Chinese democracy, and prevent a Communist takeover, all while staving off World War III.” This was the kind of thinking that led up to what would become the Marshall Plan for Europe.

And it is that kind of thinking we are looking for in the world today. That, and what we should be experiencing as we seek to commemorate the centenary of the Armistice that ended World War I. I’ve heard that a great military parade is being planned in Washington for our Veterans Day (what we formerly called “Armistice Day”). Will that parade even recognize what the day was created to honor, or will it simply be a demonstration of American military strength à la the old May Day parades in Red Square? I wonder.

Just as I wonder about the purpose – and the reception, both in America and in North Korea – about the embarrassing film put together for the recent meeting of the two leaders. It has been characterized in several different ways, but all of them seem to relate to the point of the film as being an attempt to bring the message, to the North Korean leader, that he and our president together can be the two men who will go forward to “lead the world” into a new age, putting behind us all that has come before. Could this really be – after the work and devotion of so many people and especially noticeable people like George C. Marshall – that the thinking put forward in the film is truly a goal for an international society.

I think not. I find I am particularly impressed with some of the news I’ve been reading about what Americans (some Americans) are trying to do. A strong glimmer of hope comes from The World as It Is: A Memoir of the Obama White House, by Ben Rhodes, who had been a a foreign policy adviser and speechwriter for the White House for the entire time Barack Obama was in the White House. There has been much attention given to the book, and one remark quoted by George Packer in the review of the book in The New Yorker gives us much insight as to how we can deal with what seems to be coming in our direction:

wsj.com photo

In “The Final Year,” a new documentary that focusses on Obama’s foreign policy at the end of his Presidency, Trump’s victory leaves Rhodes unable to speak for almost a full minute. It had been inconceivable, like the repeal of a law of nature—not just because of who Trump was but also because of who Obama was. Rhodes and Obama briefly sought refuge in the high-mindedness of the long view—“Progress doesn’t move in a straight line,” Rhodes messaged his boss on Election Night, a reference to one of Obama’s own sayings, which the President then revived for the occasion: “History doesn’t move in a straight line, it zigs and zags.” But that was not much consolation. On Obama’s last trip abroad [after the election], he sat quietly with Rhodes in the Beast as they passed the cheering Peruvian crowds. “What if we were wrong?” Obama suddenly asked. Rhodes didn’t know what he meant. “Maybe we pushed too far. Maybe people just want to fall back into their tribe.” Obama took the thought to its natural conclusion: “Sometimes I wonder whether I was ten or twenty years too early.”

Is that what we need to think about? Was all that came before “wrong”? Was America, as a society, not ready to move beyond the tribe. I don’t think so, and I don’t think the people I’ve been writing about here were wrong.

Perhaps it’s the times. Perhaps it’s that the right time hasn’t come yet.

Whatever happens, we have plenty to think about, don’t we?

As for what’s next, Can’t say. I’ll close here and spend the rest of this Midsummer’s Day with Act Three of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. which takes place on this very day.

Leave a Reply