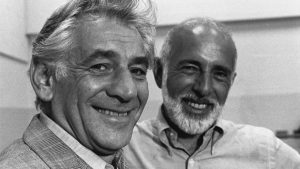

My husband Andrew and I had a couple of pleasant experiences last week. We were scheduled to see two performances at New York City Ballet, starting with an orchestra rehearsal (no dancing) on Thursday morning and a ballet performance on Friday night. To our great delight, the work of Jerome Robbins was the focus of our ballet activity for this week, and we couldn’t have been happier. We knew that 2018 is the centenary year of the great Broadway and Hollywood choreographer and director, just as it is for composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein.

When we arrived at the New York State Theater (we New Yorkers don’t like re-naming streets and our long-standing institutions, so we stick to the original and, in this case, we avoid the new name, the David H. Koch Theater), we were happy to learn from the New York City Ballet commentator addressing us that we were to hear the rehearsal on the exact anniversary of Jerome Robbins’ birth one hundred years ago, on October 11, 1918. Knowing this added a special flavor to our visit to Lincoln Center last Thursday, and all of us in the group were pleased to be there on that particular day.

We were equally pleased that our commentator would provide us with about thirty minutes of commentary about the music of two ballets. We were to hear Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun, a perfectly luscious score for which Robbins had created his own choreography in 1953 (replacing Nijinsky’s Ballets Russes original L’Après-midi d’un faune from 1912, which used Debussy’s score). The second piece on the orchestra’s rehearsal schedule was Something to Dance About: Jerome Robbins, Broadway at the Ballet. We were not familiar with this second ballet as it had premiered last May when the Robbins Centennial Celebration began at New York City Ballet and we didn’t attend any of those performances as we were traveling.

It was indeed interesting to hear about how Robbins had come to do this version of Afternoon of a Faun, for – as the story goes – Robbins had observed a young Edward Villella doing some stretches and somehow connected that action with the earlier ballet. Instead of using the entire work, Robbins choreographed a pas de deux for the music, and this beautiful piece was one of the ballets we were to have in the up-coming Friday night program.

On the Town Excerpt (1944)

After a short break, the orchestra moved forward with the rehearsal for Something to Dance About. The music for the ballet, to be performed with excerpts from Robbins’ original choreography for nine Broadway shows – going all the way back to his first, On the Town (1944) – was very well performed (with occasional pauses for Conductor Andrew Litton to request some refinement in how it was played). We left the theater looking forward to the performance of the ballet the following evening.

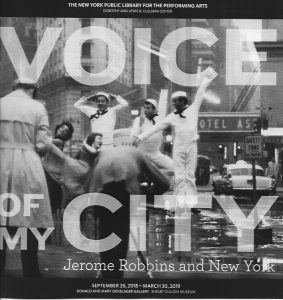

As we had taken the day off, it made sense to take advantage of something the commentator had mentioned as he spoke with us before the rehearsal. At the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts – located just across the plaza at Lincoln Center – there had just opened at the end of September what can only be described as a “monumental” exhibition. Voice of My City: Jerome Robbins and New York is an amazing compilation of material from the library’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division, covering a large space with fascinating items from both the personal and public life of this indisputably talented man.

To be in place through March 30, 2019, the exhibition’s purpose is included in the opening pages of a beautifully designed pamphlet published for visitors:

New York Public Library Exhibition Guide

Jerome Robbins was an inveterate observer, seeker, and creator. In diaries, drawings, watercolors, paintings, story scenarios, poems – and especially in dance – he reimagined the world around him. New York dominated that world, where he was born one hundred years ago and where he lived his entire adult life. Ideas of New York have long inspired artists but often the city serves as a backdrop in an artwork rather than the basis for plot, theme, and meaning. Robbins put the city at the center of his artistic imaginings. From Fancy Free – his breakout hit ballet in 1944 – to the musical West Side Story on stage (1957) and screen (1961) and the ballets N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz (1958) and Glass Pieces (1983), Robbins explored the joys, struggles, grooves, routines, and aspirations of the city and its inhabitants.

Robbins turned to New York as a source of ideas for ballets as a young man, jotting down story lines, moody set pieces, and character descriptions. One passage from the early 1940s is more of a reflection on the city itself than a story idea, more an encapsulation of the pulls and twists and yearnings that the city embodied for him, [and] he ends on a proclamation: “Have you heard the voice of my city – the poor voice the lost voice – the voice of people selling + swearing – cursing + vulgar, the shrill + the tough – the wail complaint + the defiance – have you heard the voice of my city fighting + hitting + hurt.” (Jerome Robbins Personal Papers, b.25 f.6) The passage renders the contrasts of the city from beauty to ugliness and throbs with loneliness and pain – and possession. This wounded contrary city is his.

Such an inclusive opening passage for the pamphlet’s readers makes it clear that the long life Robbins lived (he died in 1998) had both positive and great successes coupled with negative and sad, scary times. And certainly all of his successes in his profession – in the musical theater as well as in ballet – provided contrasts that will never be forgotten. There are many stories of how difficult Robbins was to get along with, and some found him so difficult that he was sometimes described as simply being evil, yet at all times he was struggling with powers in himself that appear to have brought him, too, down as far as he brought others.

Much of the two sides of Robbins’ world is described in many written articles and books, and one of the most successful tellings of the Jerome Robbins story came from Greg Lawrence (Dance with Demons: The Life of Jerome Robbins. New York: Berkley, 2001). Lawrence’s book ends with an amazing statement (“amazing” in the sense that the reader throughout the book has been doubly awed, first by the descriptions of how Robbins treated other people and, at the same time, by the descriptions of the exceptionally intellectual, honest, and sharing successes his talents contributed to the world of dance). At the end of Laurence’s book, he writes that Grover Dale – whom he described as “one of those who saw the light and the darkness in the man” – spoke about Robbins:

I’ve never known a more restless man. Watching Jerry soften at the sight of a playful dog on a beach became a lot more comforting than watching him gain strength by pointing out the weaknesses of others in rehearsals. I often wondered what the work would have been like had he been as sweet to his dancers as he had been to his dogs. Perhaps ‘contentment’ and ‘being a genius’ don’t mix very well.

If work reveals the man, Jerry showed the world who he was and what he aspired to. It’s all in there. It’s no accident that his signature work (West Side Story) was based on ‘the futility of intolerance.’ Perhaps that was the important lesson he himself was supposed to learn? Whether he learned it or not is not for any of us to say. But, thanks to his creations, the lesson about intolerance will continue to touch our lives as long as there are stages and screens to show West Side Story.

Lawrence concludes with a final statement, saying simply that in the memorials in his honor “Robbins’ memory was honored and his imperfections acknowledged by those whose lives he touched.” And his final quote was from Sono Osato, who had known Robbins since their early days together at Ballet Theatre:

He was an absolute master. His work stands as his life’s achievement. Those shows and ballets will be done over and over again through the years – probably not the way he would want them done – but they’re there for all.

Certainly that sentiment was clearly demonstrated at the following evening’s performance, particularly with Something to Dance About: Jerome Robbins, Broadway at the Ballet. But before we were treated to that exceptional work, the evening’s program began, as noted, with Robbins’ pas de deux from Afternoon of a Faun.

Other ballets in the program included Other Dances, which Robbins created in 1976, another pas de deux to music from four mazurkas and one waltz by Chopin. The program also included one of Robbins’ most famous – and popular – ballets, Moves, sub-titled “A Ballet in Silence” (1959), with the entire ballet danced without any musical connection at all, enabling the audience – as noted in the evening’s program – to engage with the movement and not to be associated with scenery, costumes, and music.

The King and I Excerpt (1951)

The evening concluded with Something to Dance About. The ballet uses Robbins choreography from nine important shows and it was all memorably performed. For this tribute, direction and musical staging was by Warren Carlyle, a Tony-award winning choreographer and director, and this program was Carlyle’s first-ever work for a ballet company. As noted in the evening’s program, these were “landmark Broadway musicals that Robbins was closely associated with during his storied career.” The shows chosen were: On The Town (1944), Billion Dollar Baby (1945), Call Me Madam (1950), The King and I (1951), Peter Pan (1954), West Side Story (1957), Gypsy (1959), Funny Girl (1964), and Fiddler on the Roof (1964).

Something to Dance About is a big show, a splashy (but dignified) production, with well-designed costumes, sets, and so forth, and since the dancing is based on Robbins’ own work, simply splendid movement from everyone on stage. The songs – when lyrics were used – were sung by the very talented Leah Horowitz, beautifully sung and of course staged perfectly. It’s a ballet designed to provide everyone involved – dancers, musicians, everyone backstage, and, most especially, the audience – the opportunity to honor Jerome Robbins, to appreciate his work and to attest to the fact that as with his shows and ballets, “they’re there for all.”

1918-1998

And is Something to Dance About a “complete” reference to all of Robbins’ life, to the downs as well as the ups, to the “devils” as well as the joys? Of course not. The ballet was not designed for that purpose, yet for all the different layers – some very obvious, some extremely subtle – what was seen and heard on the stage was unique and “special” in many different ways. And it was all summed up beautifully in the last scene, in the few lines of “Something Wonderful” from The King and I as the stunning music from Richard Rodgers and the lyrics from Oscar Hammerstein II carried throughout the theater:

This is a man who thinks with his heart,

His heart is not always wise.

This is a man who stumbles and falls,

But this is a man who tries.

This is a man you’ll forgive and forgive

And help and protect, as long as you live.

He will not always say what you would have him say

But, now and then he’ll say something wonderful.

The thoughtless things he’ll do will hurt and worry you,

Then, all at once he’ll do something wonderful.

He has a thousand dreams that won’t come true

You know that he believes in them and that’s enough for you.

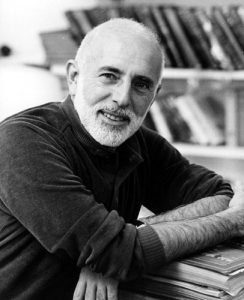

As these words – which apply as much to Jerome Robbins as to the King of Siam – were sung, a huge photograph of an older, gray-bearded, smiling Jerry Robbins was projected upstage. It was an emotional ending of a tribute to a man who, despite his flaws, showed that time and time again he was able to produce something wonderful.

Leave a Reply