On Sunday we Americans celebrate Independence Day, our July Fourth “birthday” commemorating the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It is a day on which we often try to give thought to our history, and the values that have shaped that history over the last 245 years.

Celebrating the Day

No matter where in the United States we come from, most Americans have had one or another kind of experience in observing the day. Sometimes there have been parades with bands and marching troops, other times we’ve had civil ceremonies with speeches and grand music. And certainly we’ve had – and still have – family events, picnics, drives to see distant relatives for celebrating together, a day at the beach, sporting events, and, once darkness comes, almost everywhere there are fireworks, sometimes simple, sometimes very elaborate. Sadly, in some communities, much of the celebrating has sort of faded now, and July Fourth is just another day off from work.

This probably is not the place to dwell on why the day is celebrated differently. Or not at all. Times change, people change, and as a life-shattering pandemic experience winds down – with more than 620,000 American deaths – it probably wouldn’t be appropriate anyway to dig “too deep.” Our society is strained enough as it is, and I’m not sure it would do any good to spend time lamenting what we’ve lost just because things are difficult (and different) for us.

At the same time, though, there are values in our American history that offer much consolation and even, for some of us, a kind of optimistic vision for our country’s future. Or, at least under current circumstances, some relief. For me, that idea includes giving myself over to thinking about – and listening to – music that has inspired us as citizens. There’s lots of stirring “national” music and I’ve always loved listening to it.

Listening and Thinking Back to the Past

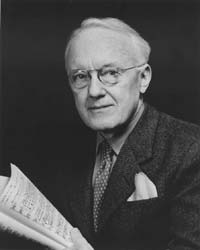

(1899-1984)

For 2021, I’m again drawn to “The Testament of Freedom” by Randall Thompson (1899-1984). It is beautiful setting for a selection of Thomas Jefferson’s words, a big work (about 25 minutes long), and musically it is kind of conservative and, at the same time, somewhat Neoclassical. I’ve loved it since I was young, for I had been exposed to it early in my life (I don’t remember the exact details, but it’s possible that I could have first heard “The Testament of Freedom” at a choral concert of one sort or another). By the time I got to the University of Virginia in Charlottesville – where this piece of music is very much appreciated – I already knew a little about it.

Until I finished my studies and left Charlottesville in 1964, I heard “The Testament of Freedom” performed several times. It was much talked about in that academic environment, especially since faculty and students of the McIntyre Department of Music placed great stock in Thompson’s work. And it had been created to be part of the university’s history, as it was composed at the request of University of Virginia President John Lloyd Newcomb who wanted to honor Jefferson as the University’s founder (1819) on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of his birth.

The texts used in “The Testament of Freedom” came from a newly published (1942) collection of Jefferson’s writings, Jefferson Himself: The Personal Narrative of a Many-Sided American. The book had been edited by Professor Bernard Mayo, teaching then at the University, and Thompson (also then teaching at the University) was asked to set it to music. It was written specifically for the University’s Virginia Glee Club, and the piece, for men’s chorus and piano, premiered on April 13, 1943, performed by the Virginia Glee Club under the direction of Stephan Tuttle, with the composer at the piano.

Sadly, with all my time at the University of Virginia, I didn’t get to sing “The Testament of Freedom.” I was invited a couple of times to audition for the Virginia Glee Club but as I was doing a lot of free-lance singing around Charlottesville – anytime a lyric baritone was called for I jumped at the chance – and I didn’t think I had the time. And as I was a student, my studies required a certain amount of my time, so I decided not to audition, and I was sorry. I would have liked to have been in the Virginia Glee Club.

The Testament of Freedom

Charlottesville VA

Randall Thompson’s composition is a four-movement work for men’s voices, since it had been written for the Virginia Glee Club and the University’s student body was, at that time, made up almost exclusively of male students (still the case when I attended the University). There were women students in the School of Education and the School of Nursing, but the University was not co-ed until 1970.

Of the many recordings of “The Testament of Freedom” available, two appeal to me. One recording is early, from 1952 (just nine years after the work’s premiere) and it is a remastered performance, directly from the mono Mercury LP, MG 50073. The performance is conducted by Howard Hanson, leading the Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra and the Eastman School of Music Chorus. It can be listened to here.

My other favorite performance of “The Testament of Freedom” is more recent, a November 2017 recording by The UVA University Singers & Charlottesville Symphony led by conductor Michael Slon. The concert took place on the stage of Old Cabell Hall at the University, the site of the world premiere in 1943. Sometime after the premiere Thompson later orchestrated the piece, and also produced an arrangement for mixed chorus, and the work is now mostly performed in this form. This is the version – for mixed voices and full orchestra – in this recording. It can be heard here.

Jefferson’s text used in “The Testament of Freedom” is as follows:

First Movement

The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy but cannot disjoin them.

—A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774)

Second Movement

We have counted the cost of this contest, and find nothing so dreadful as voluntary slavery. Honor, justice, and humanity forbid us tamely to surrender that freedom which we received from our gallant ancestors, and which our innocent posterity have a right to receive from us. We cannot endure the infamy and guilt of resigning succeeding generations to that wretchedness which inevitably awaits them if we basely entail hereditary bondage upon them.

Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great… We gratefully acknowledge, as signal instances of the Divine favor towards us, that His Providence would not permit us to be called into this severe controversy until we were grown up to our present strength, had been previously exercised in warlike operation, and possessed of the means of defending ourselves. With hearts fortified with these animating reflections, we most solemnly, before God and the world, declare that, exerting the utmost energy of those powers which our beneficent Creator hath graciously bestowed upon us, the arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverance, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die freemen rather than to live slaves.

—Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (July 6, 1775)

Third Movement

We fight not for glory or for conquest. We exhibit to mankind the remarkable spectacle of a people attacked by unprovoked enemies, without any imputation or even suspicion of offense. They boast of their privileges and civilization, and yet proffer no milder conditions than servitude or death.

In our native land, in defense of the freedom that is our birthright and which we ever enjoyed till the late violation of it; for the protection of our property, acquired solely by the honest industry of our forefathers and ourselves; against violence actually offered; we have taken up arms. We shall lay them down when hostilities shall cease on the part of the aggressors and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, and not before.

—Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (July 6, 1775)

Fourth Movement

I shall not die without a hope that light and liberty are on steady advance… And even should the cloud of barbarism and despotism again obscure the science and liberties of Europe, this country remains to preserve and restore light and liberty to them…The flames kindled on the 4th of July, 1776, have spread over too much of the globe to be extinguished by the feeble engines of despotism; on the contrary, they will consume these engines and all who work them.

—Letter to John Adams (September 12, 1821)

The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy but cannot disjoin them.

The Jeffersonian Contradiction/Conundrum

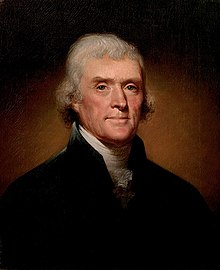

(1743-1826)

Portrait by Rembrandt Peale

As much as I love this piece of music, every time I hear it – and especially as we try to become a society more focused on some of the great failures and mistakes in our country’s history – I find myself torn by how some language used in 1775 is no longer relevant. In fact, some of it is offensive to modern ears, and I find myself having much trouble dealing with one word that in this case, Jefferson used in a totally different way from how we use it today. I’m surprised, for as a man so admired by so many of us as our intellectual and persuasive leader when it came time to bring forward our American Enlightenment, Jefferson in the second movement of this work uses the term “slavery.”

But Jefferson was not referring to what we, as a society, did with the forced laborers, the slaves we brought to America and bought and sold for economic purpose. Reading this text clearly displays a usage that refers to our colonies coming out of the bondage of pre-Revolutionary War days, of colonists freeing themselves from being forced to live under the yoke of the British. Importantly, to my way of thinking, the word is not being applied in these texts in any way to slave ownership and how slaves were used in the American colonies in those days, and that, in these times, is a problem for me.

Simply seeing the word brings forth an instinct, a reaction that offends us today. As I say, there is a problem here, a problem we have difficulty making sense of. Are we attempting to put a 2021-understanding on an eighteenth-century belief or way of life? Is the problem no more than a simple contradiction, a direct opposition between what Jefferson meant when he used the word “slavery” and what we know about the term today?

Or is our problem simply a conundrum, a puzzle that stumps us, an intricate and difficult problem or – as commonly understood – a situation where there is no clear right answer or no good solution? I spend a lot of time thinking about this, trying to “come to terms” – as I think the cliché has it – with what we know about Thomas Jefferson, and there is much here to think about.

I have tried to learn more, and over the years I have read much about Jefferson. In this case, one of the most useful documents I’ve seen comes from Monticello, Jefferson’s home outside of Charlottesville. As an educational organization, Monticello has published several works, and one of them (“Jefferson’s Attitudes toward Slavery”) is indeed helpful, noting very seriously that – even in the times in which he lived and in which he was later active as one of the country’s Founding Fathers – he himself was struggling with the overall concept of slavery. And in another account (Jon Meacham’s 2012 Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power), we learn that as a young delegate in the Virginia House of Burgesses – from age 29 to age 32 – he tried to work with reforms about slavery but he didn’t get anywhere and the overall reaction was strongly negative.

So we do have a problem, and it’s a complicated one. Jefferson owned slaves and while we would like to think of him as a caring master, of course we can’t know everything about him in this respect. And having fathered children by Sally Hemmings, the reality of the controversy becomes even more troubling.

When does a person’s “good works” become compromised, and when – if ever – can an intricate and difficult problem have a clear right answer or a good solution? We know that slavery is wrong and immoral. It always has been and always will be, but what do we do about our heroes of times past who were slave-owners?

Perhaps there is no answer.

Monticello, Albemarle County VA

Thomas Jefferson’s dates are April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826. John Adams also died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and Adams died without knowing that Jefferson had died several hours before. His last words included an acknowledgement of his longtime friend and rival: “Thomas Jefferson survives.”

Jefferson’s remains were buried at Monticello. His gravestone, with an epitaph written by him, does not mention that he was President of the United States.

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON, AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM, AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.

Leave a Reply