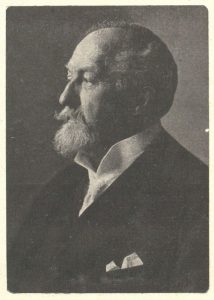

Can it be possible to prove the genius of an architect with just two adjacent apartment buildings? I think so. But that’s certainly not to say that Otto Wagner (1841-1918) did not create plenty of other examples of his genius, especially since – after an early period defined by historicism – his work moved him into a career as one of the Vienna Secession’s leading architects.

I first came to know Otto Wagner’s work on a trip to Vienna in 2006. Since then, I’ve encountered references to him and to his specific works on numerous occasions. As early as that first trip to Vienna, when I learned to associate one of the Viennese terms for Art Nouveau (Secessionsstil) with Otto Wagner, I’ve been thinking about his work. Much of my interest was influenced through a meeting with Dr. Renata Kassal-Mikula, then Director of the Wien Museum, for I was particularly pleased when she signed her book, Otto Wagner (Wien: Pichler Verlag, 2005) for me. Having her book and speaking with her about Wagner got me thinking about this talented man and his importance in Vienna’s architectural history.

Once I was aware of Wagner, I sought to learn more about him and certainly about his role in the Vienna Secession, an artistic movement that has long fascinated me. This group of artists, architects, and designers sought to modernize thinking about art and architecture. And while Otto Wagner was not one of the April 3, 1897 founders of the movement, he joined the group shortly thereafter and continued as a member until 1905. For me, considering how successful he was with the elements of Art Nouveau that I so enjoy, perhaps he represents a useful connection between Secessionism and Art Nouveau (or, as some of my friends contend, bringing the two styles together into one and the same, but I’m not sure I go along with that).

1841-1918

In any case, Otto Wagner probably continues to be the most famous of the many talented people who worked with both styles, probably not even thinking of them as such. I doubt that even an architect as talented as Wagner gave much thought to whether he was working in one style or another. During his career, as Kassal-Mikula writes, Wagner became recognized as “the great visionary of urban planning, and was certainly one of the most vital contributors to world architecture.” Much of that might be because of when and where he was born, for he was early enough and moved into his active career in the important building era which was characterized by Vienna’s most comprehensive urban renewal scheme (the ongoing Ringstrasse project and the city’s second urban expansion plan). As he moved forward with his own career, Wagner also became known as a teacher and mentor, and by 1894 had been appointed professor and director of a special architectural school at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. It became known as the “Otto Wagner School,” and it attracted major architectural talents from all over the Habsburg Empire. They joined him enthusiastically and found themselves guided by his credo which, in his ongoing struggle with traditionalists, he constantly cited: “Artis sola domina necessitas” (art knows only one master: necessity).

But can there be only one master? If we think about much of Otto Wagner’s work, necessity – it seems to me – is not the only “master.” Could not beauty be a creative person’s master as well? Can’t that also be part of the architect’s or artist’s mind-set? From where I sit, Wagner’s genius grows from both necessity and beauty, as is strikingly evident in another of my favorite Wagner buildings (and one of his most spectacular works). This is the Kirche am Steinhof, also called the Church of St. Leopold, which I wrote about in December, using the title that is now often associated with the church, “The Most Beautiful Art Nouveau Church in the World.”

Yet it is also with Wagner’s many residential buildings that the two-part “master of art” can be seen. The two apartment buildings I mention in my opening sentence are located in Vienna’s 6th District, and both were put up by Wagner (and there is actually a third apartment house close by, built at the same time at 3 Köstlergasse, although for some reason Wagner chose to execute this one in a more traditional historical style). The two residential buildings that I was so drawn to were designed (particularly the facades) to attract attention, and they did. They showed that Wagner was serious about what the Secession was looking to do to bring architecture out of the past, or even into the future, and while each house is individual, together they send a clear message about what Wagner wanted architecture to be (and do).

Relief Medallion

Linke Wienzeile

Linke Wienzeile 38, for example, certainly provides a good illustration of Art Nouveau (and with it Secessionism). Indeed, one Vienna colleague was bold enough to share his opinion with me that this residential building is recognized as one of Europe’s prime Art Nouveau jewels since it is prominently featured on the 100 Euro gold coin. And this Vienna friend went even further, remarking (using the German term for the Art Nouveau/Secession style) that “the two buildings exemplify Jugendstil.” Whatever term is used, it is easy to see why extravagant claims might be made about the building. It has an almost breath-taking facade and it is sometimes known as “the House with Medallions” because of its gilded stucco medallions, palm branches, and pendants created by Kolo Moser (1868-1918), Wagner’s student and frequent collaborator and a founding member of the Secession (he would work with Wagner again at the Kirche am Steinhof). As for the effect of the building, the overall impression is certainly one of grandeur. Notably, at one corner of the building, the entrance forms a quarter circle, an innovative touch that adds even more elegance to the building.

Linke Wienzeile 38

And for this particular building, it is possible – now that we’ve learned about the Vienna Secession and what its members were trying to do – to think of Linke Wienzeile 38 as an almost-iconic representation of their efforts and their goals. Obviously, the Secession Building is the organization’s more precise monument to what the group wanted to do, and the forward-thinking members of the Vienna Secession were quite open as they put forward their own efforts (and comments) for advancing how people should think about the arts. In doing so, they took every opportunity to “practice what they preached,” even finding encouragement from clients and patrons who supported their efforts. Or doing so themselves, as Otto Wagner (and perhaps others we don’t know about) did with these buildings, designing and constructing them at his own expense. Wagner seems to have had the habit of building several houses in a row whenever he could, acquiring large plots of land and constructing several buildings at once (these two were built in 1898 and 1899). And of special interest, the concepts all come together in an interesting bit of insight found in Kassal-Mikula’s description when she talks about the female figures at the corners above the eaves. “These ‘Voices’,” she said, “heralded the (supposed) victory of modernity which was just erecting a monument to itself in its own Secession building in the immediate vicinity.” The sculptures, also sometimes referred to as “The Criers” or “The Crying Women,” were created by Othmar Schimkowitz, who also worked with Wagner on several other commissions.

So I was not surprised, on my recent trip to Vienna, when I heard a lecture about this same building in which it was posited that the women of the rooftop were simply yelling out: “THE OLD ART IS DEAD!”

Pretty dramatic, I’d say.

Linke Wienzeile 40

The other of my pair of buildings is equally impressive but in a totally different way. This is at Linke Wienzeile 40 – also known as the Majolica House (Majolikahaus in German) – and in seeing it for the first time, the visitor is almost shocked when looking at the facade. It is, if anything, even more breath-taking than No. 38, for it is completely covered with ceramic tiles in a floral scheme using pink, blue, and green colors. Here, as Kassal-Mikula has described, the golden medallions of no. 38 are substituted by sculptured lion’s heads underneath the cornice. Majolica House is an example of Wagner’s move away from the academic historicism that was in place when he came to teach at the Vienna Academy, a transition that was not completed until well after 1900. In his textbook, Moderne Architektur, Wagner recommended using simplified designs, “the smooth surfaces in ceramic, majolica, stone and mosaics.”

Linke Wienzeile 40

Detail with Deep Cornice

Doing so became very important in international Art Nouveau, and Franco Borsi and Ezio Godoli in their Vienna 1900: Architecture and Design (New York: Rizzoli, 1986) describe why: “There were technical factors: tiles were impermeable, refractory, and resisted the chemical effects of pollution. In addition, they conformed to the standard of hygiene, since they are easily washable. Tiles were economical: Unlike cement rendering, tiles had low maintenance costs and a durability which offset the greater initial cost of materials. There was also an aesthetic factor: Ceramic coverings were regarded as the ideal accompaniment to new materials such as steel and reinforced concrete. They helped architects introduce art to design … They were the last stand against standardized and monotonous forms, anonymity, and the rejection of quality implied in the mass-production of buildings in a big city.”

Otto Wagner knew what he was doing when he recommended to his students that they should seek simplicity in their designs. Despite his famous credo Wagner brought necessity and beauty together as a dual “master” for art. It turned out to be his legacy.

Leave a Reply