As International Holocaust Remembrance Day is observed today – January 27 – two important efforts by the Chelsea Football Club are making news.

Last Thursday, as part of the club’s “Say No to Anti-Semitism” campaign, Chelsea FC unveiled a massive mural by British-Israeli artist Solomon Souza, to hang on the club’s stadium wall throughout the season, until May. A day later, Chelsea became the first sports club in the world to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of anti-Semitism. The two actions are being taken to raise awareness about how soccer (“football” in Europe) can have a significant impact as citizens and governments throughout the world step up the fight against rising threats to good citizenship and, in particular, to the increased violence and abuse being experienced throughout the world. The “Say No to Anti-Semitism” campaign is designed to raise awareness and educate players, staff, fans, and the wider community about antisemitism in football. It had been announced in January 2018 as a long-term initiative, and for the past two years, the move has been totally supported by the club’s owner, Roman Abramovich.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition states that “anti-Semitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of anti-Semitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities.” Its adoption by Chelsea comes at a very appropriate time, as the important observance of International Holocaust Remembrance Day takes on even more importance this year, coming on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. The definition, already in use by the government and the police, will be posted on the Chelsea website and published prominently in programs at each match, a level of distribution that can’t help but be taken seriously, as noted by Bruce Buck, the Chelsea chairman:

We believe that adopting the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism is an important statement for our club. Although we have been working in accordance with these guidelines for many years now, we hope that by formalizing the IHRA classification we can further tackle anti-Semitism and discrimination through better understanding and education. Football has an unrivaled ability to do good in society and we must harness this power to tackle all forms of discrimination in the stands and in our communities.

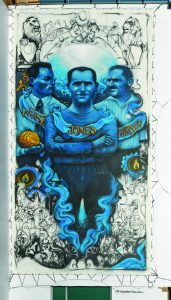

by Souza Solomon

Photo: Shahar Azran

The large mural (40-by-23 feet) shows three men linked to football who were sent to Nazi camps. It is impressive, and it could be considered equally important to the adoption of the IHRA definition. It was created by British-Israeli artist Solomon Souza, whose grandmother escaped the Nazis in 1939, and it uses the three men pictured to commemorate the unknown numbers of Jewish football players and British POWs who were sent away.

The men shown in the mural have been profiled at the Chelsea FC site:

- Julius Hirsch was a German Jewish international footballer who played for the clubs SpVgg Greuther Fürth and Karlsruher FV for most of his career. He was the first Jewish player to represent the German national team and played seven international matches for Germany between 1911 and 1913. He retired from football in 1923 and continued working as a youth coach for his club KFV. Hirsch was deported to Auschwitz concentration camp on 1 March 1943. His exact date of death is unknown.

- Árpád Weisz was a Hungarian Jewish football player and manager who played for Törekvés SE in his native Hungary, in Czechoslovakia for Makabi Brno and in Italy for Alessandria and Inter Milan. Weisz was a member of the Hungarian squad at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris. After retiring as a player in 1926, Weisz settled in Italy and became an assistant coach for Alessandria before moving to Inter Milan. He and his family were forced to flee Italy following the enactment of the Italian Racial Laws. They found refuge in the Netherlands where Weisz got a coaching job with Dordrecht. In 1942, Weisz and his family were deported to Auschwitz. Weisz’s wife Elena and his children Roberto and Clara were murdered by the Nazis on arrival. Weisz was kept alive and exploited as a worker for 18 months, before his death in January 1944.

- Ron Jones, known as the Goalkeeper of Auschwitz, was a British prisoner of war (POW) who was sent to E715 Wehrmacht British POW camp, part of the Auschwitz complex, in 1942. Jones was part of the Auschwitz Football League and was appointed goalkeeper of the Welsh team. In 1945, Jones was forced to join the ‘death march’ of prisoners across Europe. Together with 230 other Allied prisoners he marched 900 miles from Poland into Czechoslovakia, and finally to Austria, where they were liberated by the Americans. Less than 150 men survived the death march. Jones returned to Newport after the war and was a volunteer for the Poppy Appeal for over 30 years, up until his death at the age of 102 in 2019.

On January 15, in commemoration of events leading up to Holocaust Remembrance Day 2020 and with Chelsea fans and guests in attendance, the mural was unveiled during an event at Stamford Bridge, the Chelsea stadium. In his remarks, Chairman Bruce Buck said:

Millions of people were murdered during the Holocaust. As the living memory of the Second World War fades, the more important it becomes to remember the horrors that took place to ensure they are never allowed to happen again. This year is the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Our club, and our club owner Roman Abramovich, believe it is crucially important to honor this anniversary. By sharing the images of these three individual football players on our stadium, we hope to inspire future generations to always fight against antisemitism, discrimination, and racism, wherever they find it.

Leave a Reply