I have been intrigued about the First World War ever since I was a young man. I can’t pinpoint any particular reason for thinking this way – other than the fact that history, in general, has always been a subject of much interest to me. But somehow I got the notion that since I write a personal blog, colleagues and friends might like to see what I have to say about this big historical subject.

The Fourth of July, 1916 (Photo: New York Historical Society)

And as often happens with good intentions, my efforts got side-tracked. Still, there were a few offerings in my own observance of the centenary, for anyone who wants to re-visit them:

Guy’s Homage to WWI: Starting with “The Piano in Wartime: 1914-1918” (December 11, 2014)

Guy’s Homage to WWI: The Very Fine Exhibition at the New York Public Library (December 22, 2014), describing “Over Here: WWI and the Fight for the American Mind”

Guy’s Homage to WWI: Holiday Greetings from the Front (December 25, 2014), describing my little group of three hand-embroidered World War I postcards I discovered when I lived in England.

So, “best-laid plans” and all that…. It had been my goal to share my impressions about some of the things that went on during that amazing period in our history but, as I say, I didn’t get very far. I wanted to know (and think about) what we learned and how those lessons affected what we’ve become as a society. And I did spend many hours thinking about what the war meant to us, as citizens so far removed from the time of the First World War and, quite simply, as Americans. These are subjects I continue thinking about.

One of the steady themes in my life during the past few years has been my readings about the war. I started by re-reading Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August and other non-fiction titles like Adam Hochschild’s To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1918, Sean McMeekin’s Countdown to War, and many others, including Christopher Clark’s The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (brilliant, in my opinion, and the best of all the books I read on the subject).

At the same time, I was mightily impressed with several fiction titles set in the years before and during the war. Like the non-fiction, I read many of these, including one of my favorites The Dust that Falls from Dreams, by Louis de Bernieres. I also spent time with other fiction titles, including The Summer Before the War, by Helen Simonson. During the course of these anniversary years, I also embarked on a re-reading of Proust’s great work. The final volume of À la recherche du temps perdu tells us just about all we need to know about Paris during the First World War, particularly about the final days of the war, and it is a completely fascinating story.

And, as it happens, one of my favorite World War I novels was written by one of my best friends, Tom Fleming. Knowing of my interest in writing in general, and of my keen interest in writing to friends and colleagues about the war, one day at lunch Tom told me, just a year or so before he died, about how he came up with the idea for Over There, one of his World War I novels (there were several others). Going through some postcards written to the family by his father, during his service as a soldier in France during the war, Tom found references that inspired him, especially references about women in the medical services during the war. As he began searching through library shelves about the topic, he came up with his theme for Over There, completing what some consider his best fiction work (even after some of Tom’s earlier novels had been compared to William Faulkner’s, “in their intense preoccupation with a slice of American geography”). Certainly I am among those who think about the book this way, but then I am obviously a little prejudiced about Tom’s work.

As part of the general observances of of the anniversary of the war, much has been made of the artifacts associated with it. For example, at the New York Historical Society a fascinating exhibition was mounted in 2017. Called “World War I: Beyond the Trenches,” the exhibition included many important items, and from my perspective while the dramatic and often morbid war-time and battle scenes were effective, I was particularly taken (as I always am) with the display of Childe Hassam’s The Fourth of July, 1916 (The Greatest Display of the American Flag Ever Seen in New York, Climax of the Preparedness Parade in May), a favorite of all New Yorkers (and, yes, that is the painting’s real title). It is the first illustration above, at the beginning of this post.

Similar attention to wartime artifacts was given to the items in the World War I exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2017). Called “World War I and the Visual Arts,” the exhibition interestingly enough included an exceptionally wide range of materials. Described by Daniel H. Weill, the museum’s President and CEO, the exhibition included articles “ranging from expressions of bellicose enthusiasm to sentiments of regret, grief, and anger, the selected works – from prints, photographs, and drawings to propaganda posters, postcards, and commemorative medals – [to] powerfully evoke the conflicting emotions of this complex period.” Of special note were contributions from the museum’s Department of Arms and Armor. In an especially moving essay written by Donald J. La Rocca and provided to visitors (and published in the The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin), La Rocca, the Curator of the Department of Arms and Armor described in “The Met and World War I” the services of museum staff and associates in the conflict, including those who lost their lives. The essay included a photograph of the memorial tablet honoring employees who had served in World War I.

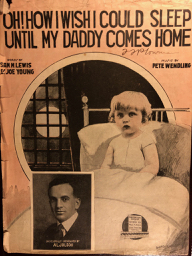

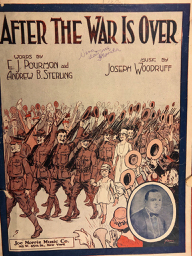

For a lighter look at some of the artifacts relating to the First World War, it’s fun to give some time to, for example, some of the sheet music being sold at the time, presumably of songs being sung in homes across America. From our family’s archives, we find several of these (and they are sadly not in very good condition, as the photos show). While all of them cannot be reproduced here, these illustrated covers tell a good story. Shown here are two I particularly liked (probably because the sentiment of each is so obviously sincere). Al Jolson, one of America’s most famous performers at the time, certainly captured the yearnings of family members for their missing men in “Oh, How I Wish I could Sleep until My Daddy Comes Home.” Equally nostalgic were the much-anticipated triumphant looks on the faces (and the stride in their march) of soldiers and their families as they expected to parade in victory when the war finally ended.

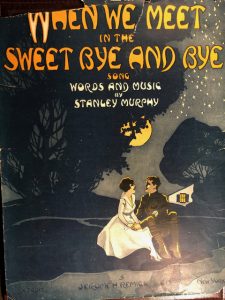

War I postcard

And if the period that produced World War I had its “romantic” flavor, it’s no surprise. Even the sheet music illustrations went beyond simple sentiment, as shown to the left, to “traditional” romantic notions. One song of the period (which shares its title with a 19th century Protestant hymn) demonstrated a yearning for a very different type of rejoicing. That Protestant hymn was about getting to the Great Beyond, and the “bye and bye” referred to the life hereafter, as characterized by the hymn’s second line (“we shall meet on that beautiful shore”). Not so Stanley Murphy’s version of triumph. His music and lyrics specifically refer to the love between a soldier and his girlfriend, and one of the prettiest things about the song is the idealism and hope depicted in the cover illustration.

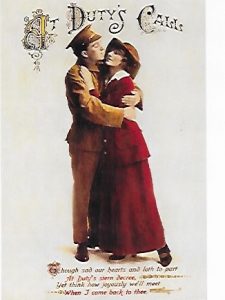

And not surprisingly, that boy-girl romantic theme was pretty universal in the allied countries, including this sweet postcard, with its appropriate doggerel (too small to be read in the photo so just for fun we’ll have it here):

Though sad our hearts and loth to part

At duty’s stern decree

Yet think how joyously we’ll meet

When I come back to thee.

French lady for soldiers to send home

And one more burst of romanticism, as we give thought to some of the emotions fitting the period. In the holiday greeting cards referred to in the 2014 link above, the postcards were made with embroidered designs on a lightweight, sheer fabric and inserted in a cardboard-like frame to make a postcard. The embroidery work was done by ladies in France, and then sold to the English soldiers (and I expect to Americans as well) stationed there. This one is particularly touching, for the front of the card, with its “Good Kisses” greeting, showed a little fabric “flap.” Inside the flap was another little card – actually very tiny – with a drawing of a young lady reaching through the barbed-wire fence to hand down to the soldiers below a ribbon-tied box of some kind of goodies, with room for the solder to sign his name, confirming his Love and Kisses. We don’t get much more romantic, even in wartime, than that.

Coming next, a few final considerations about the end of the commemorative centennial of the Armistice, with perhaps a few other thoughts to keep in mind as we seek – as a society, perhaps even as a global society – to move forward.

Leave a Reply